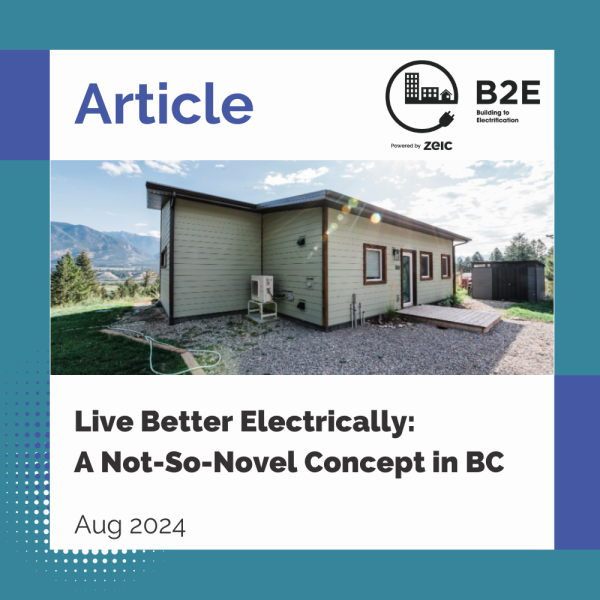

Recent media publications may have readers believing that electrifying buildings is a brand-new idea and an unreasonable endeavour. Fully electric homes, however, have been around for decades and were seen as modern since the mid-20th century. During the late 1950s through to the '70s, many newly built homes across North America displayed a Gold Medallion decal on their exterior with the tagline “Live Better Electrically.” The decal signified that the house was technologically advanced, sourced solely with electricity for heat, lighting, and power. Additional features included an electric range or built-in oven, and an electric refrigerator or combination fridge-freezer in the kitchen.

Flash forward to today; all-electric homes are once again increasing in popularity and are more energy efficient than ever. Many modern homes are built without a connection to the gas grid, and in British Columbia (BC), thanks to our clean electricity grid, these all-electric homes do not emit greenhouse gas emissions when used.

The all-electric home isn’t a novel concept; communities across BC such as Invermere and Lions Bay are not connected to gas networks and have never had access to fossil gas. Historically, homes built in these communities would likely have been heated with oil. Recent advancements in modern technology mean that a more climate-friendly solution is available; cold climate heat pumps are equipped to fill the same role as oil furnaces but without any of the emissions or air pollution. Plus, they provide heating and cooling in a single system.

There are detractors to this solution though. It’s common to read arguments that heat pumps are not able to keep up in the colder temperatures experienced in BC’s interior or northern regions.

Meredith Hamstead of thinkBright Homes in Invermere disagrees:

“For new builds in Invermere, where code minimum design temperatures are -27⁰C, this hasn’t been the case at all,” says Hamstead. “Since we first started installing heat pumps in 2015, we have found that with the right-sized design, we can easily build high-performance homes with a cold-climate heat pump as the only heating system.”

Hamstead also notes that this approach is budget-friendly, addressing another common narrative that building all-electric results in higher capital costs.

“All-electric high-performance homes can be built within a budget similar to a conventional, minimum-code-compliant home when you design for it from the outset,” she continues. “Plus, a better envelope can result in smaller mechanical systems and much lower energy bills for the homeowner.”

An all-electric new home in Invermere, BC features an air-source heat pump as the primary heating/cooling source. Photo credit: thinkBright homes

This supports findings from a recent study done by the B.C. Ministry of Housing’s Building and Safety Standards Branch that confirmed the economic viability of building all-electric homes in nearly all of BC. The study revealed that new all-electric homes can be built for virtually every budget and in any community in BC. This is good news for the Province’s Zero Carbon Step Code (ZCSC), a voluntary provincial building standard that helps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, because the most effective way to reach the highest step of this new voluntary code is to build all-electric.

Rod Nadeau of Innovation Building Group, a builder of multi-family residences in cold climates such as Pemberton and Golden, BC, notes that substantial cost savings are realized through good design practices, selecting smart building components, and right-sizing equipment. He has developed a formula for low-cost all-electric construction.

“Many people believe that it costs more to construct a building that meets the top step of the Energy Step Code and ZCSC. I found the opposite to be true. We're doing it for the same construction cost and in some cases significantly less. The mechanical systems in highly energy-efficient buildings cost less. And by not connecting to the gas network, we are saving on design, gas piping, installation, and connection charges. The residents of our buildings get the benefit of incredibly low energy bills.”

SANCO2 air-to-water heat pumps for domestic hot water. Photo credit: Innovation Building Group

The decision to go all-electric is also good for futureproofing. The province has a commitment to introduce the Highest-Efficiency Equipment Standards by 2030, which are intended to regulate the energy efficiency of the equipment used within a building. Electric resistance and heat pump technologies will both comply with this future standard, so it makes sense to build with those technologies today instead of burdening future owners with expensive retrofits.

One of the misconceptions about relying on electricity for heating is that it puts home occupants at greater risk during a power outage. The truth is that neither electric nor gas heating systems (with the exception of gas fireplaces) will operate during a power outage; most gas furnaces and boilers use components that require electricity to operate, including circuit boards, relays, blower motors, and fans.

While power outages are not a big problem in big cities, in the more rural or remote areas of BC, they can occur with greater frequency and longer duration than in urban areas. According to Nadeau, “We do not need a backup heating system for our homes. People living in them provide about 1/3 of the heat required at our design temperature of -22⁰C. We turned the heat off in some of our apartments in the winter to see how they performed, and it took a week to drop from 22⁰C to 16⁰C. This ability to maintain a fairly constant indoor temperature without power makes power outages trivial from a thermal comfort perspective.”

The reason why an energy-efficient building can maintain the indoor air temperature during a power outage is because of its building envelope. Adding a thick layer of insulation, for example, or installing highly energy-efficient windows and doors is a passive strategy that will result in better heat retention and improve overall building efficiency. This is true for both new construction and existing buildings, regardless of the heating fuel type. Wally Martin of Langley, BC, describes his motivation for choosing an all-electric passive house.

“As a builder for many years I am very aware of the advantages of all-electric homes,” states Martin. “Electricity is cleaner and more adaptable in any application. Given the negative climate impacts of burning fossil fuels and the risks of leakage, explosion, and carbon monoxide poisoning, we did not want gas in our home. We installed an air-to-water heat pump that easily supplies all our domestic hot water and space heating needs.”

“Our design is a passive house and little or no cooling is required,” Martin continues, describing how design helps. “We have a heat recovery ventilator (HRV) to provide fresh air and in the summer, we open windows at night to cool our home. Our insulated concrete slab foundation is heated in the winter which can keep us warm for many days, so we didn’t feel that there was a need for a back-up heating source.”

Main floor interior features a beam ceiling, an energy saving feature that reduces interior and exterior wall height, reduces heat loss, and uses less building material. Photo credit: Wally Martin

As a further illustration of resilience, Nadeau notes, “The all-electric OSO building in Golden performed great this past winter when we had some -40⁰C nights and the all-electric Orion building kept cool during the 2021 heat wave that ranged between 41⁰C and 48⁰C for a week. We now have data to show that our all-electric buildings work well from -40⁰C to 48⁰C, which we believe can serve most climate zones in Canada.”

For homeowners living in cold and rural communities, a supplementary heating system, such as a wood stove, might be used to stay cozy and warm during extreme cold snaps. Karen Barkley, the owner of the mostly all-electric thinkBright-built home featured in this video, considered the potential power outage risk and opted to include a small wood stove as a secondary system in her home design.

A small wood stove serves as supplemental heating on extremely cold days. Photo credit: thinkBright Homes

“I’m really happy with my heat pump, it keeps me comfortable in the winter and now I have cooling for the summer,” she says. “My heat pump is rated to -25⁰C, although it does seem to work at temperatures lower than that. There are a number of really cold days each winter and the extra boost of heat from the wood stove helps. I use the stove about 10 days each winter, and likely only need it for six.” Thinking ahead she adds, “In the future, I plan to invest in solar panels with batteries to improve the resilience of my home.”

All-electric homes are not a novelty in BC; in fact, they’re becoming more common and are a proven part of BC history. With modern construction strategies, sustainable building practices, and materials innovation, they are a feasible and effective option for reducing impact on our climate while keeping us comfortable and safe.

All-electric homes have earned their place as part of our past, present and future.

A B2E publication written by Mariko Michasiw, B2E Program Manager, with input from the B2E ABC Committee.

b2e@zeic.ca

b2e@zeic.ca